Obsession is the mother of perfection. It is this magic madness we have to thank for the most astounding machines and the highest mechanical technologies gracing our precious planet. And we may bless those madmen for their genius and their drive to achieve the impossible.

In our fantastical world of high technologies, with daily discoveries of new frontiers in science, medicine and computers, there is too little time and opportunity to understand where the seeds of all this wonder began.

It was long ago. Much of it began with an unrelenting obsession to measure the passing of time in the finest increments possible, long before there was any practical application or need. This passionate pursuit of the mastery of time developed into the fascinating science of horology, which has given us those rare treasures of technology and art.

The earliest attempts to mark time go back to prehistoric humans. Ancient tribes in every continent celebrated the positions of the stars, Sun and Moon in rituals that guided their lifepaths. For them, time was a spiraling cycle of daylight and night, of moon phases, or months, and of sun positions through each year. The ticking split seconds of a modern stopwatch were unfathomable for at least the first 80,000 years of human existence on earth.

At Stonehenge they captured the point of sunrise in midsummer and the day of the winter solstice, by axes.

Egyptian sundials date back to 2000 B.C., but it was not until the middle ages that Arab astronomers and mathematicians mastered the complex calculations required to make humble instruments accurate through varying seasons. These true sundials were still not common in Europe until the end of the 15th century, by which time mechanical clocks were in their infancy, most of them incapable of matching the accuracy of the sundial.

The ultimate expression of the sundial was the amazing astrolabe, the world’s first scientific instrument. Its origins go back to ancient Greece, but the research and craftsmanship that refined it were primarily in the Middle East around 1000 A.D. This instrument provided both latitude and time of day, serving navigators well until the middle of the 18th century, when the quadrant was born.

Mechanical timekeepers and the high art and science of horology are a phenomenon of the Millennium we are about to close. Early mechanical clocks were somewhat philosophical in nature. As tools in the unraveling of the mysteries of the universe they attempted to aid our understanding of nature’s mysteries and our desire to control her moon phases and seasons. However, these early timepieces had very little hope of measuring time with any useful degree of accuracy. Water clocks, sand clocks and incense clocks, some of enormous proportion and complexity, were fanciful indulgences of horological visionaries. They were patronized by rulers with wealth and competitive ambition far beyond any semblance of reason or practicality.

Even cultures that abhorred punctuality were driven to create clocks. In ancient Japan it was an unconscionable insult to expect anyone of importance to meet at a specific time. When an appointment was made, several days before and after the appointment were also reserved. The individual of a lesser stature would arrive well before the scheduled time frame and wait patiently until the host (of greater stature) was ready to consummate the engagement.

The Japanese did not lose their independence from time until they became enmeshed in the Industrial Revolution and finally had to succumb to the conformity of the Western world to keep their trains on schedule and their time clocks punching out the minutes and hours of each individual’s productivity.

Up until this period Japanese clocks were made with adjustable dials to match the length of day of the seasons. Each month the clockmaker would come around and move the hour markers on the clock dial to create shorter or longer hours to match the period of daylight and darkness. Since it was customary to work from sunrise to sunset, it was logical to adjust the length of the hours to the period of daylight.

As logical as this appears, the rest of the world was hell-bent on dividing the year into exact increments and keeping track of every moment. This proved to be a formidable task, challenging and honing the intellect and skills of philosophers, mathematicians, engineers and artisans for more than a thousand years. These driven horological masters created hundreds of new technologies in their pursuit of elusive and ever smaller increments of precision timekeeping. With the magnificent achievements man has wrought from these last thousand years, it is ironic that one of the most intimidating challenges we face is the timely transition of the feared Y2K. One might say that we have made such demands on the science of time that we are now its slaves and cannot rest in our service of its demands.

The mysteries of horology have teased and challenged the greatest minds of history. Nearly every great philosopher and inventor of the ancient world wrestled to understand and unravel the passage of time and sought how to harness this powerful force.

As if he weren’t busy enough concocting impossible technologies 400 years ahead of their time and contracting for monumental works of art, most of which would never be completed, even Leonardo da Vinci could not resist the temptation of designing clockwork mechanisms.

As with most of his inventions, it is unlikely that any of Leonardo’s clocks were ever built in his lifetime, but he left us with three of the most important engineering features of the modern clock – the escapement, the pendulum and the fusée. Like so many of Leonardo’s great discoveries, the concept of the pendulum and escapement was lost and would linger in obscurity for 150 years before it was rediscovered and revolutionized the science of timekeeping.

The pendulum and escapement allowed clockmakers to control gear trains with a new level of accuracy by interrupting the progress of the movement in even increments.

The fusée became the most elegant form of transmission ever designed, with the ability to compensate for changes in torque throughout the power range of the driving spring. This increased the accuracy of clocks and watches exponentially and became a standard feature in every fine clock and watch from the 17th century to modern times. Like so many other technologies developed by horologists, the fusée and escapement found its way into thousands of industrial uses through the ages.

Up until the 19th century the primary machines civilization required were clocks, watches and firearms. These were the Space Age challenges of the day in that they required materials and fabrication techniques that did not exist.

The creation of these new technologies spawned the manufacturing age and the industrial revolution, changing our world forever.

Watch and clockmaking were the highest of the mechanical arts, constantly elevated to new heights by fierce competition and intense one-upsmanship among the aristocrats of Europe. Most of the engineering, tooling, machining and metallurgical sciences we use today were developed, of necessity, in the clock and watch industry.

The finest, most complex and mind-expanding mechanical achievements found in the world’s museums today are products of the single most common drive of 18th century aristocracy – boredom.

Nobility of this era suffered from a plague of pampering. Life at court was so absurdly burdened with servants to perform every daily function that there was nothing left to do for oneself. There were attendants to dress you, feed you, bathe you, transport you, entertain you and generally ensure that you did little or nothing by your own efforts.

Short of political espionage, the most exciting sport of the gentry was to upstage each other with the newest and finest work of their treasured artisans. With this goal in mind they put immense pressure and no shortage of patronage on the finest craftsmen of the day to create the most spectacular toys on earth.

These amusements ranged from magnificently jeweled precision watches and clocks to musical snuff boxes, singing bird automata and watches with risqué menàge-á-trois animated erotic scenes hidden under the back cover, performing in tempo to the quarter-hour chimes, usually with the castle hound looking on with envy.

This whimsical and fantastic genre of amusements for royalty gave free rein to the genius of masters like Breguet, Faberge, James Cox and hundreds of inspired artisans fortunate enough to find favor in the courts and win commissions or favors in exchange for satisfying the insatiable appetite of the elite. One famous watchmaker and ladies man of the French court, having been caught red handed with a nobleman’s wife, was saved from the gallows by promising the King he would make him the finest watch he had ever seen – clearly a man who knew how to use his talents to great advantage under a variety of circumstances.

Each time a new level of artistry and complexity was achieved, the ante was raised for the court craftsmen to outdo the competition. This rivalry among the rich left us with a world of magnificent timepieces no craftsman could have produced with his own limited resources, a lesson we should apply to our modern world. It has always been the pleasure and responsibility of those who have amassed substantial wealth to patronize the arts, providing artisans with the means, purpose and opportunity to exercise their ultimate talent.

Beyond curiosity and amusements, horology has influenced the destiny of civilization. Many horological creations have helped to carve the course of history, creating empires which have fathered the culture of the western world and affected civilizations across the globe. The clearest and best known example of this is the invention of the marine chronometer by John Harrison. This is a remarkable story in its own right and one told most eloquently in the recent best seller Longitude by Dava Sobel.

John Harrison was a miraculously gifted carpenter who devoted his entire life to solving one of the greatest problems of history: the ability to establish longitude at sea.

Through his dedication and perfectionism, he created the world’s first marine chronometer, a machine capable of measuring time through the rigors of stormy seas with astounding accuracy far beyond that previously achieved on stable land.

This critical advantage of navigation, which had eluded every navy of the world for centuries, gave England the means to conquer the seas and develop their small island into the greatest world power of the 19th century.

With no formal horological training and the most unorthodox methods, Harrison demonstrated a unique inventive genius and mechanical intuition that has yet to be improved upon today.

Following this extraordinary trail to the end of the rainbow, one of the true pleasures of collecting these timely treasures is the discovery of a world of craftsmanship beyond the imagination of modern times. When you hold an 18th century example of the watchmaker’s art in your hand, you experience a level of engineering, fabrication and artistry which only an elite handful of craftsmen in the past century have recreated.

Every encounter with one of these masterpieces is an enlightening and humbling experience one can relive a thousand times with new levels of appreciation. Only a select few clock and watchmakers today are capable of creating timepieces that rival these. When they do, their works are highly prized.

For those of us who are not content to read about or view these wonders through the glass of museum showcases, it is fortunate that opportunity still exists to acquire, restore and preserve these treasures in our private collection and estates.

Few people in today’s world are aware of the fact that magnificent clocks and watches from the 18th and 19th centuries are available today at a fraction of their intrinsic value. It is not unusual to purchase a high-grade 18th century watch in today’s market for $5,000 to $10,000 that would cost $75,000 in man-hours to produce (and would have cost that much in terms of earning power when it was new). Clocks fall into a similar category of value and are among the best bargains in the antique investment market.

Although true collectors buy timepieces primarily because they love them, it is a nice side benefit that good clocks and watches appreciate in value at a healthy rate, creating a nice portfolio over the years. More than a few collectors have retired quite comfortably, after selling off their collections in their sunset years.

It is quite easy to develop a healthy addiction to clocks and watches. There are hundreds of good books on the subject and thousands of passionate collectors who love to show off and talk about their most prized treasures. Within six months of buying their first timepiece, most collectors are solidly hooked and on their way to a lifelong love affair with their horological treasures.

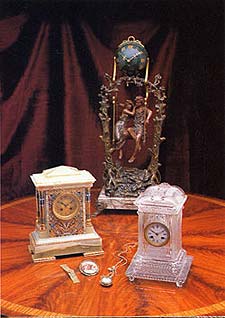

One of the great joys of collecting clocks and watches is the infinite variety encountered in the quest. The highly competitive nature of the industry and the demand for ever more complex and unusual timepieces has driven clockmakers in every corner of the globe to ethereal levels of ingenuity and refinement.

Many collectors focus on very specific types of clocks or watches, sometimes those of just one maker, while others prefer an eclectic mix with as many types of timepieces as they can squeeze into their homes or offices. In either case, it is always most rewarding, aesthetically and financially, to buy the finest and rarest specimens you can afford.

These special pieces are the ones that will become rarer with time and grow both in interest and value with each passing year, assuring that you’ll count your hours amid the best times of life.

Building a clock or watch collection is a rewarding lifetime hobby that can be enjoyed by anyone with an appreciation for history, aesthetics, fine craftsmanship and innovative mechanical design.